Birth of the UK National Debt…

… or the world’s first stimulus bill

|

| From the National Maritime Museum |

Jeake stared tentatively at the English ship, and the speed with which it was approaching indicated it was on the run. This could mean only one thing: the French were coming to sack Rye. Others who had seen the same frightful sight rang the church bells and alerted the occupants of Rye to pack their belongings and flee the town. Chaos ensued. The town only had one exit and soon people trampled each other, clamoring for their escape.

The English ship limped to the beach. The captain, not wanting his ship to fall in French hands, set the ship alight. Unto this day, if the sea is right, the skeleton of the burned ship surfaces on the beaches of Rye, as a ghost resurfacing to tell of a terrible time when England was at the mercy of its worst foe.

[CONTINUES BELOW]

|

| Battle of Beachy Head 10 July 1690 |

|

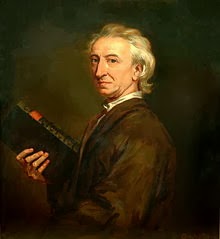

| John Evelyn |

The whole nation now exceedingly alarmed by the French fleet braving our coast even to the very Thames mouth;wrote diarist John Evelyn. But the French did not fully pursue, a tactical error that would deprive the French of a major long term victory.

This meant that the English were able to mobilize 90 ships by the end of August and break the French control over the channel. But it also meant that the weakened English fleet could no longer adequately protect its merchant ships on their trade missions while defending its shores. In the years to come, this would cost the English dearly. English sailors filled their ships with the nations hard earned trade, said goodbye to their families, and unprotected by the navy, set sail for exotic destinations, hoping to make their fortune. And they never returned… They were probably captured or destroyed by the French or commercial raiders.

Fear paralyzed the hearts of seamen the merchants, and, by 1692, trade missions ground to a halt, sucking the life blood out of the English economy.

The recession deepens

Goods destined for trade now accumulated in the English harbors without ever being sent out, in fear of capture and destruction. |

| Winston Churchill |

[...] we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle [...] .But of course, there was no mighty British fleet. Instead, despair and hunger turned into an active move of defiance: 0n the 30th of May 1693, the merchants organized themselves to break the impasse in a bold and risky move. 200 merchant ships would band together and undertake a trade mission to Smyrna, Turkey. On board was a year's worth of trade that had just been sitting in the harbors: wool, tin, spices and silver, the richest trade mission the world had ever seen. But it also presented a most alluring prize to the enemies of the Kingdom.

|

| King William III |

French spies had uncovered the particulars of the mission, and having decided against an invasion of England in favor of a war against English commerce, they positioned 93 of their war ships further up at Lagos Bay, at the southern tip of Portugal.

On June the 27th of 1693, the unsuspecting merchant flotilla, under command of George Rook, sailed into the French trap. Waiting for them was the French fleet, commanded by their old enemy Admiral Tourville. In the past, Tourville had once had a chance to destroy the might of the English navy, but passed up on it. Tourville smiled. He had been shamed for his blunder 3 years ago, and here was a chance to remake his name.

|

| George Rooke |

He ordered two Dutch ships under his command to buy the fleet time by engaging the French war ships directly. The crew of the Zeeland and the Wapen van Medemblik set course for the French and prayed to their God to be merciful on their souls.

It must have been an odd sight, these two lonely ships approaching the might of a 93 strong French war engine. Tourville cursed. He had hoped for the greatest of victories: that the merchant fleet would band together and could slowly be ground down by his war machine. Instead, the ships in front of him dispersed in all directions. He ordered pursuit.

|

| Admiral Tourville |

Despite this display of death-defying bravery and the good judgment of Rooke, the French still captured or destroyed almost 100 merchant vessels.

The news hit England and sent the merchant classes in despair. A wave of bankruptcies ensued. The economy, already on its knees, fell on its face.

A national effort to raise money

King William the 3rd needed a navy to protect English trade missions and he needed it fast. In its current state, there was no way it could protect the English shores and the trade missions simultaneously. But the coffers were empty and the economy was so depressed that raising taxes might lead to revolt and further economic malaise. Something else had to be done.King William the 3rd was the son of a Dutch father and an English mother. At birth he was destined to be King of Holland. As the king of Holland, he had learned two things. One was the power of the Navy, which had been instrumental in the invasion of England and had overthrown his father in law, the English King James II during the Glorious Revolution. The other key piece of insight he'd picked up lie in the financial revolution that the Dutch had brought the world: the world’s first stock market. Created almost a century before in 1602, citizens could now invest their hard earned money into corporations, and in exchange receive a return on their investment.

Perhaps this Dutch innovation could be a way to mobilize the battered riches of the country?

Working together with Scotsman William Patterson, the creation of The Bank of England was proposed in 1694. Anyone willing and able to put in 25 Pounds would get a guaranteed 8% return on his investment. The return was so appealing that both the wealthy and the poor invested their savings in the bank. A look at the book of investors in the Bank of England reveals not only the names of the King and Queen, who invested 10,000 pounds, but also the names of historical actors whose names we recognize from this blog post: John Evelyn and Samuel Jeake. When Jeake first heard the news he immediately gathered up all his riches and traveled on horseback for 15 straight hours from Rye to London. Saddle sore, tired and hungry, he arrived in London and without resting and went straight to his financial agent to discuss the investment. Browsing through the book, we see something even more fascinating: the names of 9 people who were in domestic service who invested every hard-earned dime they had into the bank. This was truly a country-wide effort, where everyone who had money poured it into the bank of England.

In just 12 days it raised 1.2 million pounds, and on August the 4th, it made its first loan to the government.

|

| Ship of the line |

More than half of the first loan went to building up the navy which had the fortunate side effect of transforming the English economy. Each navy ship required over 5 tons of iron nails, 2000 trees, 7000 square yards of canvas and 10 miles of ropes. The navy soon employed 44,000 men, feeding them from a reinvigorated English agriculture. Building the ships made South England into the navy’s building yard, North East Britain into the world’s first industrial iron works (providing the nails) and soon the navy became the engine of English commerce. In 10 years, the navy was 176 ships strong and soon became the sole rulers of the sea.

But that is a story for another day.

Birth of the UK National Debt…

Reviewed by Unknown

on

4:05 PM

Rating:

Reviewed by Unknown

on

4:05 PM

Rating:

Reviewed by Unknown

on

4:05 PM

Rating:

Reviewed by Unknown

on

4:05 PM

Rating:

No comments: